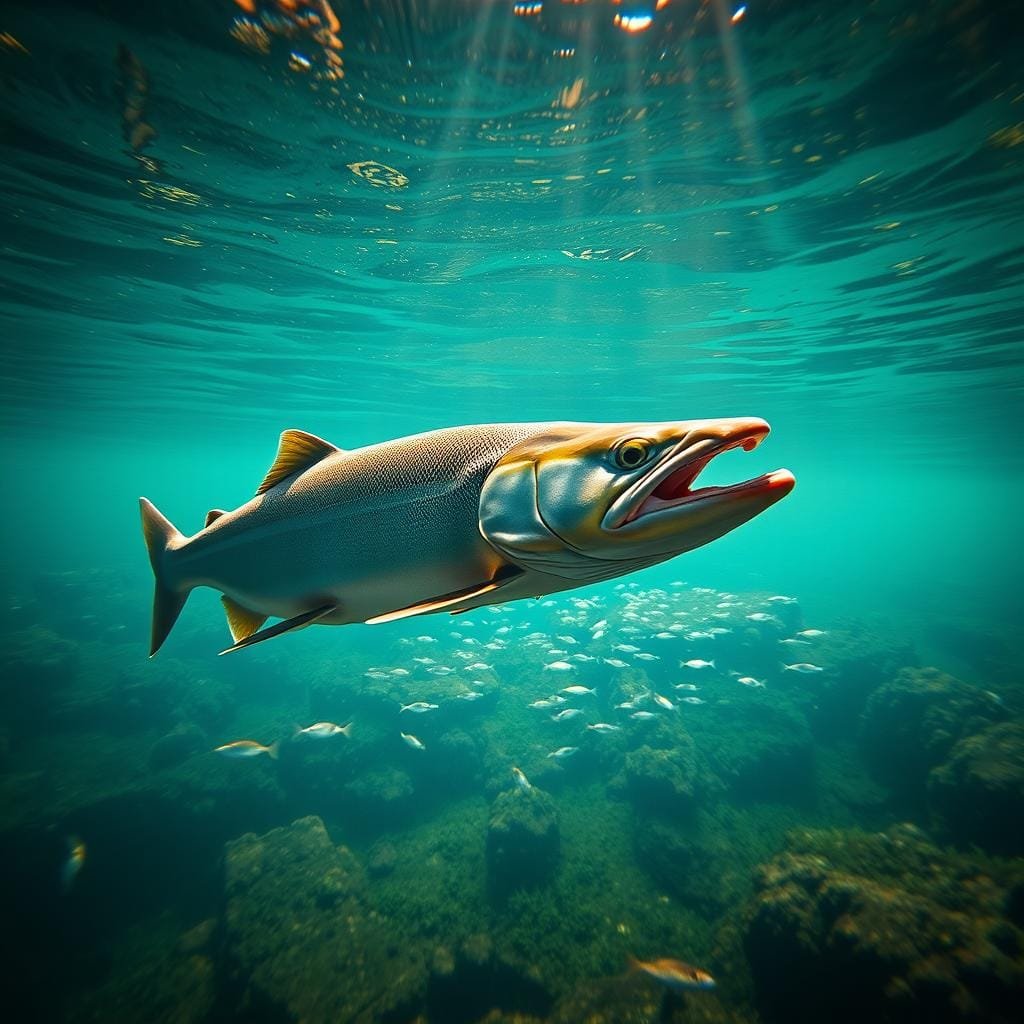

Ever wonder what lake trout eat in America? They start small and grow big. Lake trout eat tiny food as young ones and big prey as adults. This change makes them big and why fishermen love to catch them.

Young lake trout eat zooplankton, insects, and small crustaceans like opossum shrimp. As they grow, they eat more fish like lake whitefish and sculpin. They also eat smaller lake trout and sometimes even small mammals.

Season changes their hunting style. In spring and fall, they hunt in the water’s top layers. But in summer, they go deep, sometimes as deep as 600 feet. Their big mouth helps them catch a lot of food, making them very big.

Where they live affects what they eat. They need cold water and lots of oxygen to thrive. Big lakes with plenty of food and smart hunting make them big. This also affects other fish in the lake.

Lake trout basics: species, names, and native range

Big, marble-backed fish that live in cold water are often called “trout.” But the lake trout char is different. Anglers from Duluth to Anchorage know it by many names. Its story is about ice-carved basins and inland seas in the Great Lakes and beyond.

Scientific identity: Salvelinus namaycush (a char, not a true trout)

The lake trout char is scientifically known as Salvelinus namaycush. It belongs to the char family in the Salmonidae family, not true trout. The name “namaycush” means “dweller of the deep,” fitting its love for cold, clear water.

It has cousins like Arctic char and brook trout. They share traits like pale spots and white-edged fins. This is because they live in frigid lakes.

Common names in the U.S.: lake trout, Mackinaw, togue, grey trout

In the U.S., you might hear Mackinaw trout in the West, togue in New England, and grey trout among guides. Many just call it “lake trout” or “lake char.” They all point to the same fish: Salvelinus namaycush.

Regional names often tell a story. The name Mackinaw came from stocking efforts. Togue stuck in Maine and the Adirondacks.

Where they live: Great Lakes, deep cold lakes in the Upper Midwest and Northeast, Alaska

Their home is the Great Lakes and deep, cold lakes in the Upper Midwest and Northeast. They also live in Canada and Alaska. They prefer water near 50°F with lots of dissolved oxygen.

They move through the water column with the seasons. Whether you call them lake trout char or Mackinaw trout, they need big, cold, and clean water.

| Identity | Key Traits | Regional Names | Core Range | Habitat Needs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salmonid (char) | Pale spots, white fin edges, deep-water adapted | Lake trout, Mackinaw trout, togue, grey trout | Native range Great Lakes; Upper Midwest; Northeast; Alaska | Cold (~50°F), clear, high oxygen (~4 ppm) |

| Salvelinus namaycush | Long-lived, slow-growing, apex predator | Also called lake char in some regions | Northern U.S. to Arctic Canada | Deep basins with stable thermoclines |

What does lake trout eat

Ask any guide about lake trout food and they’ll say a simple rule. Start small, eat bigger as they grow. Lake trout food changes with size and the lake’s conditions. Knowing this helps understand their eating habits through the seasons.

Juveniles: zooplankton, insects, and invertebrates

Young lake trout eat tiny things. They munch on zooplankton, midge larvae, and mayfly nymphs. In northern waters, Mysis shrimp are a big energy source for them.

Biologists say small trout eat invertebrates when they’re plentiful. See more about young lake trout feeding on invertebrates.

Adults: predominantly fish—whitefish, cisco/tullibee, burbot, sculpin, smaller lake trout

Adult lake trout eat fish as they grow. They mainly eat whitefish, cisco, burbot, sculpin, and sometimes smaller trout. This change helps them grow fast and explains why they eat what’s plentiful in the lake.

When fish gather in deep water, adults go after them. They look for oily, high-energy food. This makes them grow quickly and strike hard, even in 100 feet of water.

Opportunists: crustaceans, midges, ants, and the occasional small mammal

Even big lake trout are flexible. They eat midges near the surface at calm evenings. Windy shores can bring ants that attract them. Crayfish and Mysis shrimp are also on their menu when they’re around.

Some reports say they even eat small mammals. This shows how varied their diet can be when they want to.

How diet changes as lake trout grow

Lake trout change what they eat as they get bigger. This is a common thing that anglers notice. At first, they eat small things. Later, they start to eat bigger, more energy-rich fish.

From invertebrate feeders to apex piscivores

Young lake trout eat zooplankton, insects, and Mysis. As they grow, they start to eat soft-rayed fish and sculpins. By the time they are about two feet long, they mostly eat other fish.

In the Great Lakes, their diet changes too. They start to eat alewife, cisco, and round goby. Young ones mostly eat Mysis and other small creatures. For more on this, see this Great Lakes diet change summary.

Size of prey increases with trout size and jaw capacity

As lake trout get bigger, they can eat bigger fish. Small ones eat slender baitfish. Big ones go after bigger fish like whitefish or cisco/tullibee.

- Small trout: zooplankton, insects, Mysis near structure and open-water edges

- Medium trout: smelt, small sculpin, young-of-year cisco

- Large trout: adult cisco, whitefish, round goby pulses in spring and fall

High-calorie prey and the path to trophy size

Cold water makes digestion slow. So, lake trout need food that’s full of calories. Oily fish like cisco and whitefish help them grow big over time.

| Life Stage | Primary Foods | Feeding Mode | Energy Return | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Juvenile | Zooplankton, insects, Mysis | Pursuit of small swarms | Low per bite | Sets the base of the ontogenetic diet shift lake trout exhibit |

| Subadult | Smelt, small sculpin, young cisco | Mixed tactics, edge cruising | Moderate | Growth and prey size begin to scale with gape |

| Adult | Alewife, cisco, whitefish, round goby | Ambush and open-water runs | High | Piscivory dominates; efficient calorie capture |

| Trophy | Large cisco/whitefish, seasonal goby loads | Energy-maximizing strikes | Very high | Trophy lake trout diet depends on stable big-lake forage bases |

Studies show that lake trout’s diet changes with the seasons. Round goby is more common in cool months. Alewife peaks in warm water, making feeding more efficient.

Seasonal feeding patterns and depth

Lake trout eat based on water temperature, oxygen, and food. As the water gets colder or warmer, they move. They go from shallow areas to deeper ones, sometimes right up to the surface. Anglers can guess where they are by checking water temperature, wind, and light.

Spring and fall: roaming the water column and into the shallows

In spring and fall, trout swim in cold water. They go from the top to the bottom, looking for food. They like to be near shore where smelt and other fish are.

On calm days, they come up to warm rocks. They eat a lot at dawn and dusk. They look for easy food near rocks and where the water moves fast.

Summer: holding deep in cold, oxygen-rich water (often 50–200+ feet)

In summer, trout stay deep because of the thermocline. They like water 50–200 feet deep in big lakes. In very clear lakes, they can go even deeper.

When it’s sunny and bait is plentiful, trout get hungry. They swim in schools, making it easy to catch them. They eat a lot when there’s a lot of food and oxygen at their depth.

Ice-out and midge hatches: surface feeding opportunities

After the ice melts, trout swim near the surface. Wind brings insects to shore. A slow-moving lure can get them to bite hard.

In calm evenings, trout eat midges. They rise to the surface, making it easy to catch them. Dry flies work well during these times.

| Season cue | Typical depth | Primary behavior | Effective approach | Why it works |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early spring (ice-out) | Surface to 20 ft | Shoreline cruising | Small streamers, minnow plugs, slow swimbaits | Cold, uniform temps pull bait shallow; trout roam edges |

| Late spring to early summer | 20–80 ft | Roaming breaks | Flutter spoons, swimbaits, slow-trolled crankbaits | Prey funnels along structure before deep stratification |

| Mid-summer | Summer depth 50–200 feet | Thermocline holding | Lead-core trolling, downriggers, vertical jigs | Stable cold, oxygen-rich water concentrates fish and forage |

| Calm midge evenings | Surface | Midge hatch trout sipping | Dry flies, emergers, soft hackles | Dense insect clusters trigger surface feeds in low wind |

| Windy fall days | Surface to 40 ft | Spring shallow lakers pattern returns | Spooned jigging, stickbaits along rocky points | Cooling water reopens the full column; bait rides waves into shore |

Habitat factors that shape the menu

Lake trout like water near 50°F with lots of oxygen. This lets them chase prey for a long time. In cold lakes with lots of oxygen, they hunt more.

By midsummer, they go deeper to find food. They eat cisco, whitefish, burbot, and sculpin. Big lakes with deep areas offer more food.

Size of the lake affects trout. Small lakes have less trout but bigger ones have more. When food is plentiful, trout grow fast.

| Habitat Driver | Key Threshold | Effect on Diet | Where It Happens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature + Oxygen | ~50°F and dissolved oxygen 4 ppm | Supports active hunting in cold oxygen-rich lakes | Thermocline layers in deep oligotrophic systems |

| Basin Morphology | Large, glacial deep basins forage pathways | Aligns trout with cisco, whitefish, burbot, sculpin | Great Lakes, Lake Superior inland analogs |

| Forage Concentrators | Humps, sunken islands, gravel bars, flow | Boosts prey availability in tight zones | Points, saddles, and current-influenced breaks |

| Zooplankton Base | Mysis-rich layers at depth | Feeds juveniles, stabilizes early growth | Clear, cold lakes with strong invertebrate bands |

| Carrying Capacity | Biomass ~2–4 lb per surface acre | Lower density, larger individuals when forage is high | Remote northern lakes and deep reservoirs |

Predatory behavior and notable prey encounters

Guides from Scott Lake to Great Bear Lake tell amazing stories. Big fish come up from the dark with their fins spread wide. They move fast, then stop on a dime to catch their prey.

Ambushes and open-water cruising “like sharks”

Cory Craig and Tom Klein say trophy lakers hide near reefs. Then, they slide off to catch schools. They can be tight to structure or cruising deep like sharks.

When bait scatters, they chase fast. Their strike is from below, with their mouth open wide. This is how they hunt, using sight, stealth, and speed.

Pike, whitefish, and even smaller lakers on the menu

Adult lakers eat whitefish and cisco/tullibee. But they also eat burbot, sculpin, and even northern pike. Tom Klein and Brad Fenson have seen this happen.

They even eat smaller lakers when food is scarce. They use the same ambush-and-sprint tactic for these smaller fish.

Why big lakes make big, fish-eating trout

Anglers say big lakes have big trout for a reason. Great Bear Lake has a 72-pound record, and Lake Athabasca had a 102-pound giant. These lakes are cold, have lots of space, and plenty of bait.

In these places, fish grow big and strong. They cruise like sharks every day. This leads to many exciting moments for anglers.

Forage species profiles in American waters

Lake trout live in deep, cold lakes. They eat oily fish and bottom dwellers. The food they choose depends on the depth, water clarity, and temperature.

Lake whitefish and cisco/tullibee: oily, energy-rich staples

Coregonines are key in the whitefish cisco diet. They are full of lipids, giving trout lots of energy. In the Upper Great Lakes, trout follow schools of lake whitefish and cisco/tullibee.

When winds blow, bait moves toward structure. Trout follow, crashing through schools. This is common in the Great Lakes, from Michigan to Minnesota.

Burbot and sculpin: benthic prey in deep basins

Trout eat burbot and sculpin in deep basins during summer. These fish live near the thermocline, hiding in cobble, clay, and soft mud. They are slow and easy to catch in the dark.

Anglers who fish the bottom often catch bigger fish. The best spots are where the bottom drops off into basin flats.

Opossum shrimp (Mysis) and other crustaceans for juveniles

Young trout eat tiny meals first. Mysis shrimp are a big part of their diet. Where opossum shrimp bloom, young trout feed in clouds.

As they grow, their diet changes. They start eating perch fry and small coregonines. But crustaceans are important in clear, deep water. On calm evenings, midges and ants add quick calories near the surface.

| Forage | Primary Zone | Energy Value | Best Trout Life Stage | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lake whitefish | Midwater to near-bottom over basins | High lipid, oily | Adults | Anchors the whitefish cisco diet in the forage fish Great Lakes mix |

| Cisco/Tullibee | Open water, schools near breaks | High lipid, oily | Adults | Drives pelagic feeding runs during cool-water periods |

| Burbot | Benthic, deep basins | Moderate to high | Adults | Nocturnal burbot prey aligns with summer depth patterns |

| Sculpin | Rocky bottom, drop-offs | Moderate | Adults | Sit-and-wait sculpin prey targeted along structure transitions |

| Mysis (Opossum shrimp) | Water column at dusk/night | Moderate protein | Juveniles | Mysis shrimp lake trout growth driver before full piscivory |

| Insects/Terrestrials | Surface and shoreline | Variable | All sizes opportunistically | Ice-out midge slicks and summer ants add quick bites |

Trout eat everything from oily fish to tiny crustaceans. This helps them survive in big, cold waters. By understanding their diet, anglers can find them in the Great Lakes.

Angler takeaways: matching the hatch for better bites

Start by reading the forage. To match the hatch lake trout, pick profiles that mirror whitefish and tullibee. Choose lake trout lures with big, reflective scales and a slim, tapered body. Brad Fenson likes cisco imitation crankbaits for mid-depths, matching local baitfish.

Spoons are great. Flutter spoons for lakers flash on the drop and thump on the pull. Many salmon models work well for lake trout. Williams spoons are good for fast, high-visibility retrieves on bright days.

Think about location and timing. Start shallow in spring and late fall. Work rocky shorelines, shoals, and staging areas as fish move in with cool water. In late spring to summer, go deep to cold, oxygen-rich layers.

Break down structure. Mid-lake humps, sunken islands, gravel bars, and subtle current can hold fish. Position above these rises, sweep cisco imitation crankbaits through high spots. Yo-yo flutter spoons for lakers along breaks.

Watch for brief surface feeds. In calm June evenings, midge hatches can pull trout up top. A dry fly attractor works when rises dimple the slick. Right after ice-out, cruise shorelines for fish sipping ants.

Gear for a brawl. These fish have big heads and wide jaws for large prey. Expect long runs and torque. Use strong braided main line with a fluorocarbon leader to protect lures, and set drags smooth for battles.

Conservation notes: diet, growth, and ecosystem impacts

Lake trout are long-lived salmonids that grow slow and mature late. Many do not spawn until age five or older. Some skip years between spawns. They can live up to 62 years, like the record from Kaminuraik Lake.

This slow growth makes them vulnerable to overfishing risk. If too many older fish are removed, reproduction drops fast. Conservation plans protect these mature fish while keeping prey communities intact.

Diet and growth patterns shape lake ecosystems. Young lake trout eat invertebrates. Adults eat other fish and can change food webs. Introduced populations have harmed native salmonids, like the Lahontan cutthroat trout in Lake Tahoe.

The most famous example is the invasive impacts in Yellowstone. Lake trout hurt the Yellowstone Lake cutthroat run. This affected bear, eagle, and otter diets.

Habitat limits also matter. Lake trout need cold water and 4 ppm dissolved oxygen. This limits biomass to about 2–4 pounds per surface acre in many systems. Protecting large, deep, cold lakes helps forage like cisco and whitefish. This supports apex predators.

Records show what intact habitats can yield. A 102-pound netted giant is the biggest caught. This shows what conservation can achieve when it aligns with food supply and stable age structure.

Management follows the biology: slot limits, seasonal closures, and focused control where they are nonnative. This balances goals. Knowing their diet shift helps set rules to protect breeders and avoid prey crashes.

When agencies pair harvest plans with habitat work, they reduce overfishing risk. They curb invasive impacts Yellowstone style. This keeps these long-lived salmonids on track for the next generation.